A continuación publicamos la réplica que se ha dado desde el Círculo Carlista Felipe II de Manila a la conmemoración oficial denominada «Día de la amistad hispano-filipina»

(traducción al español más abajo)

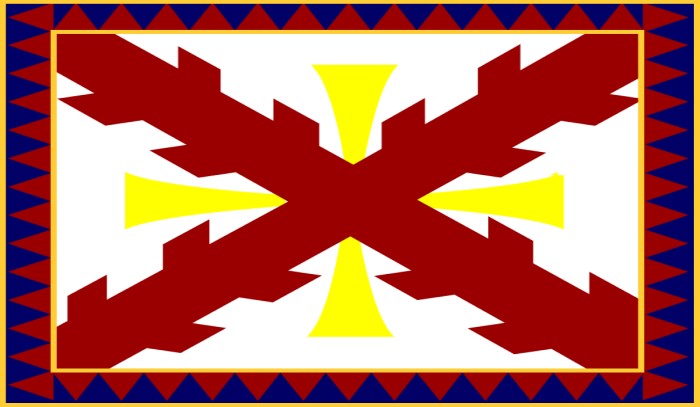

June 30th is declared to be «Filipino-Spanish Friendship Day». There has been circulation all over social media of the oil on canvas painting by the utopian dreamer Juan Luna. It consists of a woman in red with a laurel wreath in her hair representing Spain pointing to a distant chimerical horizon to a woman in native dress who in turn looks longingly to that eternally wishful horizon. Nothing can be more devoid of supernatural symbolism than such ephemeral frivolity.

The truth of the matter is that the real Filipino-Spanish friendship already took place. It was called «Las Españas» (the Spains). The Philippine Archipelago is as Spain just as Castile and Aragón are. So were all viceroyalties such as New Spain (México/Méjico), Perú, Río de la Plata, and New Granada.

The true friendship between them was nothing other than the true christian coexistence between different peoples under one catholic monarch where there was a recognition of the true Church as the one and only means of salvation and catholic unity was the ground of true social order.

We can safely say that the epitome of Philippine Christian civilisation and real brotherhood, where the Reign of Christ the King was realised, took place in the 17th Century. The situation in the Philippines at the end of the 17th century was very positive and the progress experienced by the country was great. The Filipinos were happy and full of encouragement. This optimism is accurately reflected by the Augustinian missionary, Martínez de Zuñiga, in his Estadismo:

«The Spanish domination has brought very few burdens to these Indians, and has freed them from many misfortunes… After their conquest their happiness and their population have increased, and it has been very useful for them to have been subject to the king of Spain in everything that concerns the body; I say nothing of the advantages of knowing the true God and finding themselves in proportion to procuring eternal happiness for the soul because now I am not writing as a missionary, but as a philosopher (Cfr. J. Martínez de Zúñiga, Estadismo de las Islas Filipinas, p. 73)».

Those responsible for this progress, who had radically changed the country, were the Spanish missionaries. Ordinarily, they were the only representatives of the Spanish government in the provinces. Knowing the people and the language, they enjoyed a great reputation. Their prestige was the prestige of Spain. Tomás de Comyn, at the beginning of the 19th century, speaks of the well-being and tranquility of the country and of the agents responsible for it:

It happens in fact that since the parish priest is the consoler of the afflicted, the peacemaker of families, the promoter of usefulness in the islands, the preacher and example of all that is good; since freedom shines in him, and the Indians see him alone in their midst, without relatives, without traffic, and always busy in his greatest promotion, they get used to living happily under his paternal direction, and they give him their complete trust (Cfr. Thomas of Comyn, State of the Philippine Islands, Manila, 1877, pp. 147-148).

Tomás de Comyn again praises the achievement of the friars in the Philippines, and the work they were doing when he visited the country at the beginning of the 19th century:

Go to the Philippine islands, and you will be amazed at the vast countryside of spacious churches and convents; at the splendor and pomp of divine worship; at regularity in the streets, at cleanliness and even at luxury in costumes and houses; schools of first letters in all the villages, and very skillful inhabitants in the art of writing, to open roads, to built bridges of good architecture, and the punctual fulfillment in most of the provinces of good government and police work; all the combined work through sleepless nights, apostolic works and accentuated patriotism of the ministers. Walk through the provinces, and you will see towns of five, ten and twenty thousand Indians peacefully governed by a weak old man, who opens his doors at all hours and sleeps peacefully in his room, with no other magic and no other guards than the love and respect he has been able to instil in his parishioners (ibidem).

The truth is not only based on quotes from authors. It is justified in itself, but in order to get to know it, one has to analyze sources from the past. One more quotation, this time from an Englishman, reaffirms not only the work of the missionary in the Philippines during the Spanish period, but also the prestige that they still enjoyed well into the 19th century:

The degree of respect the «padre» has among the Indians is indescribable. It approaches almost adoration. And the father has earned it by his own hand… One must accept, to his honor, that the conduct of these reverend fathers justifies and gives title to the trust they enjoy. The «padre» is the only defense against the mayor’s oppressions. The «padre» protects, advises, consoles, denounces and defends his flock. He has often been seen, hunched over by the passing of years and illness, leaving his province, beginning a long and dangerous journey to Manila to present himself as an arbiter for the happiness of his people with all the means at his disposal (An Englishman Remarks on the Philippine Islands, 1819-1822, p. 211).

All this was possible because of the fostering of true friendship among nations by means of true supernatural charity and solicitude for souls which was exhibited by the first king of the Philippines. When discouraged by his advisers who did not approve the Spanish intervention in the Philippines due to its high cost and low benefit, finding nothing that would compensate for such a great work, King Philip II replied: «But there are souls».—Pero hay almas.

In another instance, the true supernatural spirit that moved Philip II can be found in the answer he gave to those who advised him to abandon the Philippine Archipelago, in view of the little revenue they brought to the Crown. He said:

«For the conversion of only one of the souls that are there I would willingly give all the treasures of the Indies, and if they were not enough I would add those of Spain. Nothing in the world would make me consent to cease sending preachers and ministers of the Gospel to all the provinces that have been discovered, even if they are barren and sterile, for the Holy Apostolic See has given to us and our heirs the apostolic commission of publishing and preaching the Gospel. The Gospel can be spread through these islands, and the natives can be drawn from the worship of the demon by making known to them the true God, in a spirit alien to that of temporal greed».

Juan Carlos Araneta, Círculo Carlista de Felipe II de Manila.

(versión en castellano)

El 30 de junio se ha declarado como «Día de la Amistad Filipino-Española». Ha circulado por todas las redes sociales el óleo sobre lienzo del soñador utópico Juan Luna. En él aparece una mujer vestida de rojo con una corona de laurel en el pelo que representa a España señalando un lejano y quimérico horizonte donde se encuentra una mujer vestida de indígena que a su vez mira con anhelo ese mismo horizonte eternamente deseado. Nada puede estar más desprovisto de simbolismo sobrenatural que esa frivolidad efímera.

Lo cierto es que la verdadera amistad filipino-española ya ha tenido lugar en el tiempo. Se llamaba las Españas. El archipiélago filipino ha sido tan España como lo son Castilla y Aragón. También lo fueron todos los demás virreinatos de la Monarquía hispánica como Nueva España, Perú, Río de la Plata y Nueva Granada.

La verdadera amistad entre ellos no era otra cosa que la verdadera convivencia cristiana entre diferentes pueblos bajo un mismo monarca católico. En las Españas se reconocía a la verdadera Iglesia como único medio de salvación y la unidad católica como fundamento del verdadero orden social.

Podemos afirmar sin temor a equivocarnos que el epítome de la civilización cristiana filipina y de la verdadera hermandad en la que se hizo realidad el reinado de Cristo Rey fue el siglo XVII. La situación en Filipinas a finales de dicho siglo era muy positiva y el progreso experimentado por el país era grande. Los filipinos estaban contentos y llenos de ánimo. Este optimismo lo refleja con precisión el misionero agustino Martínez de Zúñiga en su Estadismo:

«La dominación española ha acarreado muy pocas cargas a estos indios, y los ha librado de muchas desgracias…Después de su conquista se ha aumentado su felicidad y su población, y les ha sido muy útil el haberse sujetado al rey de España en todo lo que concierne al cuerpo; no digo nada de las ventajas de conocer el verdadero Dios y hallarse en proporción de procurar una felicidad eterna para el alma porque ahora no escribo como misionero, sino como filósofo». (Cfr. J. Martínez de Zúñiga, Estadismo de las Islas Filipinas, p. 73).

Los responsables de este progreso, quienes cambiaron radicalmente el país, fueron los misioneros españoles. En la práctica ellos eran la única representación del gobierno español en provincias. Conocedores del pueblo y de la lengua, gozaban de un gran renombre. Su prestigio era el prestigio de España. Tomás de Comyn, a principios del siglo XIX, habla del bienestar y tranquilidad del país y de los agentes responsables del hecho:

«Sucede efectivamente, que como el párroco es el consolador de los afligidos, el pacificador de las familias, el promotor de las islas útiles, el predicador y ejemplo de todo lo bueno; como resplandece en él la libertad, y le ven los indios solo en medio de ellos, sin parientes, sin tráficos, y siempre atareado en su mayor fomento, se acostumbraron a vivir contentos bajo su dirección paternal, y le entregan por entero su confianza». (Cfr. Tomás de Comyn, Estado de las Islas Filipinas, Manila, 1877, pp. 147-148).

Tomás de Comyn vuelve a alabar la lograda por los frailes en Filipinas, y la labor que estaban realizando cuando él visitó el país a comienzos del siglo XIX:

«Váyase a las islas Filipinas, y se verán con asombro sembradas sus dilatadas campiñas de templos y conventos espaciosos; celebrarse con esplendor y pompa el culto divino; regularidad en las calles, aseo y aun lujo en los trajes y casas; escuelas de primeras letras en todos los pueblos, y muy diestros sus moradores en el arte de escribir, abrirse calzadas, construirse puentes de buena arquitectura, y darse en fin puntual cumplimiento en la mayor parte a las provincias de buen gobierno y policía; obra todo de la reunión de los desvelos, trabajos apostólicos y acendrado patriotismo de los ministros. Transítese por las provincias, y se verán poblaciones de cinco, diez y de veinte mil indios regidas pacíficamente por un débil anciano, que abiertas a todas las horas las puertas, duerme sosegado en su habitación, sin más magia ni más guardias que el amor y respeto que ha sabido infundir a sus feligreses». (ibídem).

La verdad no sólo se basa en citas de autores. Se justifica en sí misma, pero para llegar a conocerla hay que analizar fuentes del pasado. Una cita más, esta vez de un inglés, reafirma no sólo la labor del misionero en Filipinas durante el período español, sino también el prestigio de que gozaban todavía bien entrado el siglo XIX:

«El grado de respeto que tiene el «padre» entre los indios es indescriptible. Se acerca casi adoración. Y el padre se lo ha ganado a pulso…Hay que aceptar para honra suya, que la conducta de estos reverendos padres justifica y les da título a la confianza que gozan. El «padre» es la única defensa contra las opresiones del alcalde. El «padre» protege, aconseja, consuela, denuncia y defiende su rebaño. Con frecuencia se le ha visto, encorvado por el paso de los años y de la enfermedad, dejar su provincia, comenzar un largo peligroso viaje a Manila para presentarse como abogado en pro de su felicidad con todos los medios a su disposición». (An Englishman Remarks on the Philippine Islands, 1819-1822, p. 211).

Todo ello fue posible gracias al fomento de la verdadera amistad entre las naciones por medio de la verdadera caridad sobrenatural y la solicitud por las almas que exhibió el primer rey de Filipinas. Cuando sus consejeros le indicaban que no convenía aprobar el asentamiento español en Filipinas por su alto coste y escaso beneficio, al no encontrarse allí nada que compensara tan magna obra, el rey Felipe II respondió: «Pero hay almas».

En otro caso, el verdadero espíritu sobrenatural que movía a Felipe II se vio en la respuesta que dio a quienes le aconsejaban abandonar el archipiélago filipino, en vista de los pocos ingresos que aportaban a la Corona. Dijo:

«Por la conversión de una sola de las almas que allí se encuentran daría de buena gana todos los tesoros de las Indias, y si no fueran suficientes añadiría los de España. Nada en el mundo me haría consentir en dejar de enviar predicadores y ministros del Evangelio a todas las provincias que se han descubierto, aunque sean estériles y baldías, pues la Santa Sede Apostólica nos ha dado a nosotros y a nuestros herederos el encargo apostólico de publicar y predicar el Evangelio. El Evangelio puede ser difundido por estas islas, y los nativos pueden ser sacados del culto al demonio dándoles a conocer el verdadero Dios, con un espíritu ajeno al de la codicia temporal».

Juan Carlos Araneta, Círculo Carlista de Felipe II de Manila.